The Golden Age cricket bat

In November 2010, a remarkable cricket bat was offered for sale by Christies in London, England with an estimate of around $25,000 to 40,000 USD. Although the bat featured on the cover of the auction catalogue and was described in the auctioneer’s notes as ‘a more profusely autographed bat than any other sold in these rooms,’ the bat failed to sell.

Eighteen months later, in May 2012, the same bat was offered for sale in Melbourne, Australia by Leski’s auctions, a specialist in cricket memorabilia and although the estimate was reduced to around $20,000 to 27,000 USD and the owner was willing to pay for ‘insurance and delivery cost free to anywhere the purchaser requires’, the bat was passed in, once again.

Unlike the tiny ashes trophy that takes pride of place at the MCC Museum at Lords, the Golden Age cricket bat most probably remains in the owner’s ‘bank safe in England’ (according to the auctioneeer’s notes), but in may have something in common with the treasured terracotta urn - the bat may have also once belonged to a woman, and on a personal note, one that lived and died in the same London suburb (Wimbledon) in which I was born.

The Golden Age of cricket was an era that began with the first season of the English county championship in 1890 and ended with the outbreak of world war one in 1914. It was an period rich in sportsmanship, verve and innovation, a game that was thriving on an enthusiasm that swirls around that of T20 cricket today.

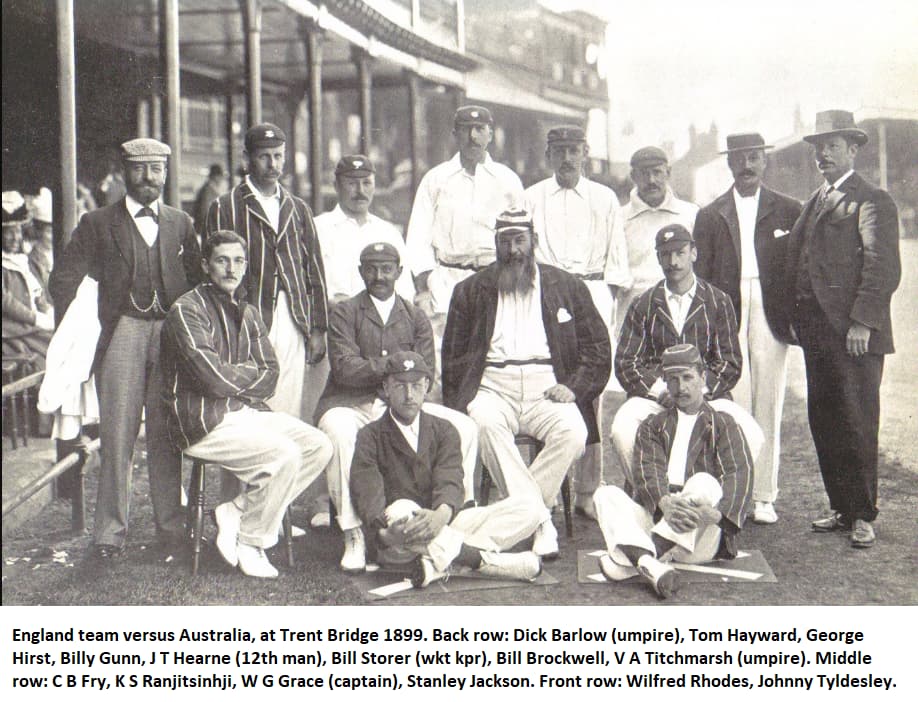

The colossus of the age was WG (William Gilbert) Grace, a phenomenal cricketer who scored over 54,000 runs and took over 2,800 wickets over forty-four summers, a trailblazer who set so many records along the way. Grace was fifty when he played his last test match at Trent Bridge in 1899 and it is possible, perhaps probable, that the golden age cricket bat was originally his, given that Grace’s signature appears in the ‘ownership position’, on the reverse side at the top of the bat.

In total, there are 211 signatures on the bat, autographs that were collected around the turn of the 19th century. They include fifteen Australian and sixty-five English test players. All bar one of the English players in the photograph commemorating Grace’s last test match below have signed the bat.

They include K S Ranjitsinhji, an Indian prince and the first from the subcontinent to play international cricket, Ranjitsinhji was one of the most innovative batsmen in history and India’s domestic first-class competition, The Ranji Trophy, India’s domestic competition for first-class cricket is named in his honour.

C B Fry was the ultimate ‘all-rounder’ who played both cricket and football for England. Fry played for Southampton in a F.A Cup final, he equalled the world record for the long jump and even in his seventies, he claimed he was able to perform his party trick of leaping from a stationary position, backwards, onto a mantelpiece!

Tom Hayward was one of the greatest batsmen of all time, scoring over 1,000 runs in first-class cricket for an astonishing twenty years in succession and he remains one of only twenty-five men to score one hundred 100’s in first class cricket. (Before you click on the link, a quick quiz question: There is only one Australian, West Indian, Pakistani and New Zealander on the list. Qudos to you if you can name them!)

Like ships passing in the night, Wilfred Rhodes made his debut in Grace’s last test and went on to forge a career spanning over five decades (1899 to 1930), ultimately surpassing the doctor as the oldest to play a test match at the age of fifty-two! Rhodes holds world records for most appearances in first-class cricket (1,110 matches), most wickets taken (4,204) and did the double of 1,000 runs and 100 wickets in an English cricket season a record sixteen times.

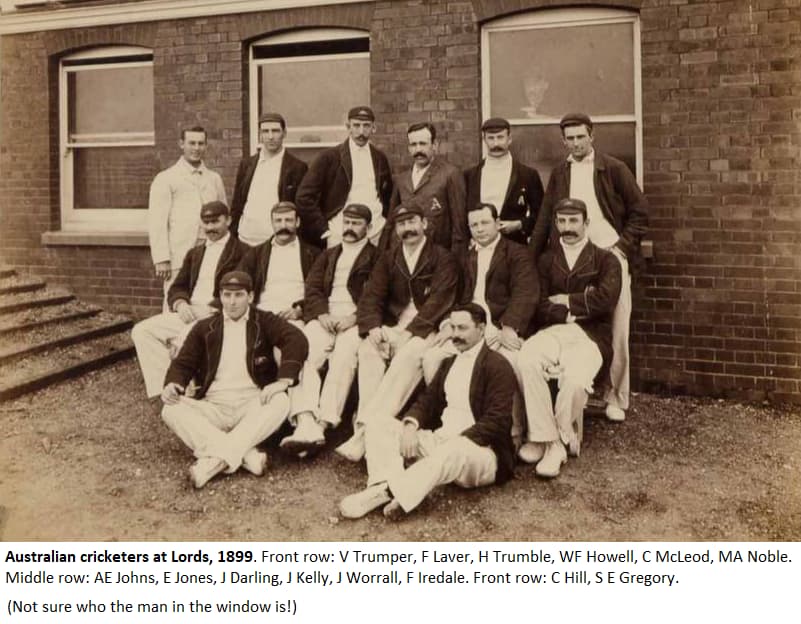

The Australians of 1899 were equally iconic. Of the fifteen Australian signatures on the bat, five captained their country whilst six are members of The Australian cricket Hall of Fame.

This includes the inimitable Victor Trumper, the first man to achieve the rare feat of making a century on the first morning of a Test match. Such was Trumper’s popularity that when he died at the age of thirty-seven, 250,000 mourners lined the route of the largest funeral procession ever seen in Sydney.

Like Trumper, M A ‘Monty’ Noble is another honoured with a stand at the Sydney Cricket Ground, an all-rounder who excelled at every facet of the game. Clem Hill was a batting maestro and the son of H. J. Hill, who scored the first century on Adelaide Oval, his son setting so many batting records on the oval that the ground named a stand in his honour.

Fred ‘The Demon’ Spofforth was Australia’s original fast-bowling tearaway and the first man to take a test hat-trick, fifty of his 94 test wickets were bowled. WG Grace considered Spofforth to have been the original inventor of ‘swerve’ or ‘swing’ bowling.

On both sides and even along the edges of this unique cricket bat, the signatures of Golden Age titans abound. There’s Gilbert Jessop, the original ‘Bazballer’, whose record for the fastest test ton by an Englishman in 76 balls has stood for over 120 years and was set at a time (1902) when a boundary clearing the rope was still only four.

S.F. ‘Syd’ Barnes was one of the greatest bowlers of all time. He played in 27 tests and took 189 wickets at 16.43, one of the lowest Test bowling averages ever achieved. BJ Bosanquet was the inventor of the googly. CJ Burnup and SH Day, were first-class cricketers and footballers for England. J Daniell was a county cricketer and captain of the England rugby team. RE ‘Tip’ Foster made the highest score by a Test debutant, a mighty 287 at Sydney in 1903 and still the highest score by an Englishman in Australia.

Sir Pelham ‘Plum’ Warner was a test cricketer, administrator and the youngest of 21 children. Warner was the Manager of England during the controversial Bodyline series in 1932-33 and when he expressed his sympathy after play to Bill Woodfull, the Australian captain famously told him ‘I do not want to see you, Mr Warner. There are two teams out there. One is playing cricket and the other is not.’

Remarkably, the collector of the signatures remains a mystery (as does the current owner of the bat) but could another amazing cricket bat with 169 signatures from the same period and known as ‘The Bardswell Bat’, hold vital clues? Is it possible that both bats belonged to a cricketing authoress who lived at number 7 The Crescent, in Wimbledon?